Chapter III |

||

OPERATIONS |

||

The Battle of the Atlantic |

||

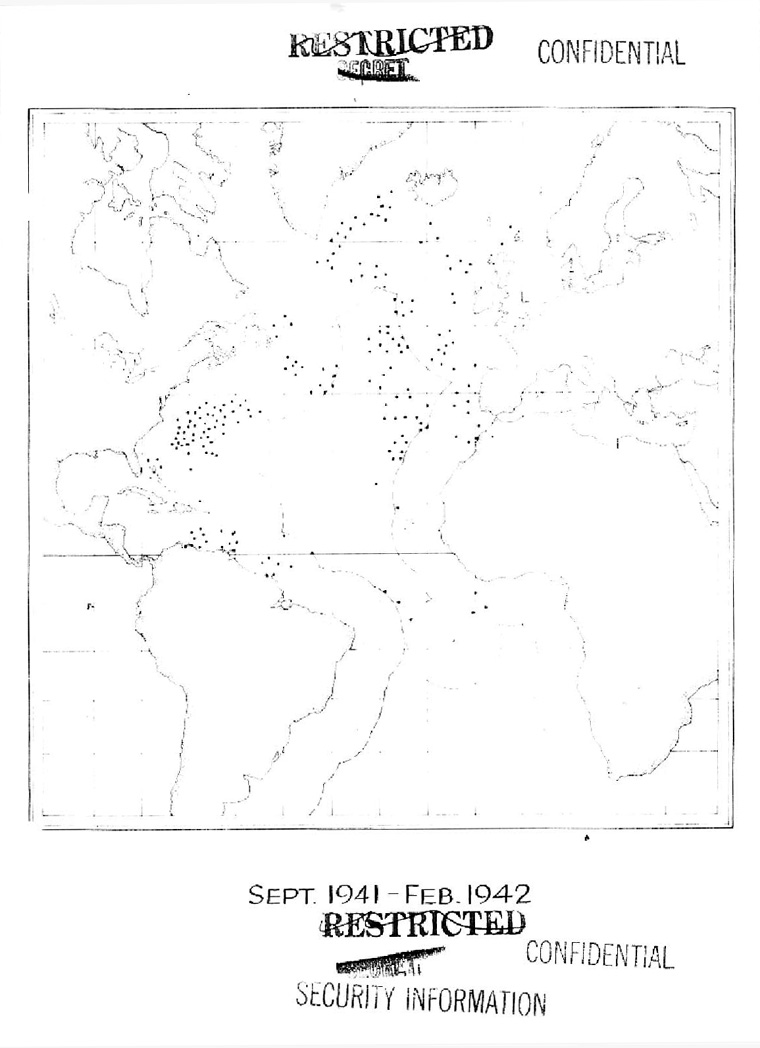

| It was a large and already crowded stage onto which the AAF Antisubmarine Command stepped in October 1942. The Battle of the Atlantic had not yet reached its peak of intensity, nor had any decisive blows been struck, but several phases of the conflict had already come and gone and several agencies were engaged in an effort to defeat the Nazi raiders. At first, in 1939 and 1940, the U-boats had operated with impunity close to the British Isles and the coast of Europe. The British had made every effort to counter the submarine blockade and had, in fact, cleared the English Channel and North Sea waters with fair success. As yet, however, aircraft were used only to a limited extent, and long-range air patrols were unheard of. The result was that the U-boats moved farther field, scattering their attacks as far west as 49°, and as far south as Africa. Effective air patrol remained relatively short-ranged, leaving the whole central ocean a free hunting ground for the enemy. | ||

| The next phase of the battle began upon the entry of the United States into the war. The resulting depredations off the U. S. Atlantic coastline General Marshall felt jeopardized the entire war effort. | ||

87 |

||

| By the middle of June 1942, he reported that 17 of the 74 ships allocated to the Army for July had already been sunk, 22 per cent of the bauxite fleet, and 20 per cent of the Puerto Rican fleet had been lost, and tanker sinkings had amounted to 3.5 per cent per month of the tonnage in use.1 | ||

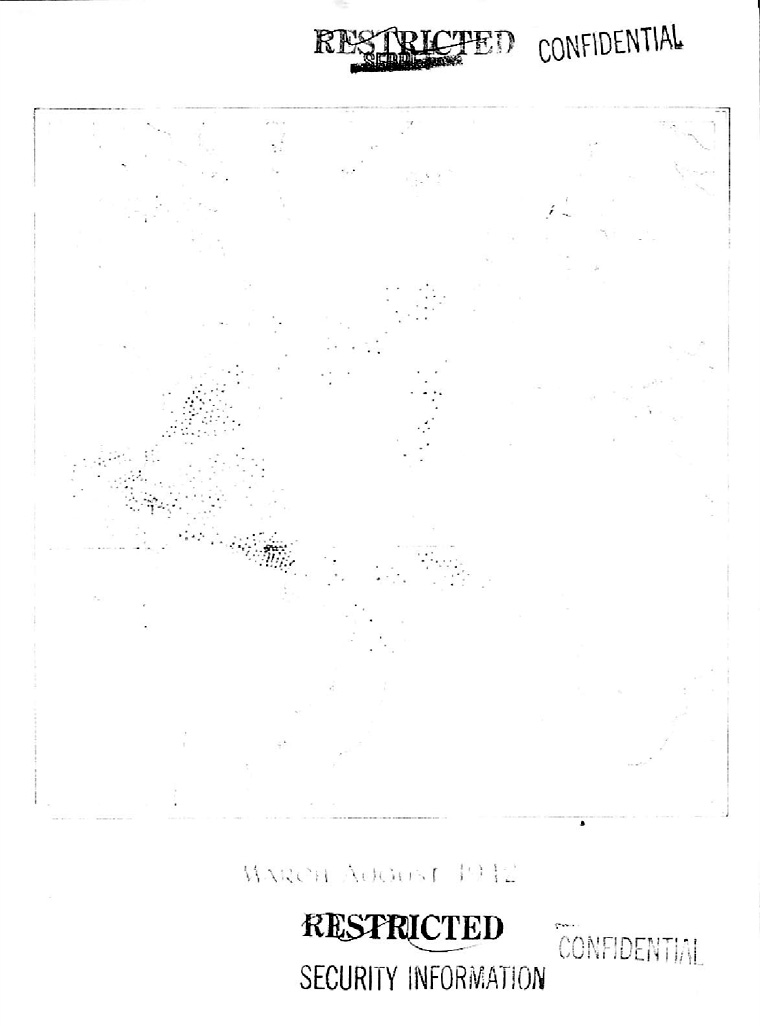

| By the fall of that year an entirely new act in the drama was begun. The enemy had gradually withdrawn from the Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers, partly because of the increased opposition he encountered in American waters and partly because the Allied invasion of North Africa made it essential for the U-boat fleet to turn from its aggressive campaign against shipping in general in order to operate defensively against the invasion convoys. The U-boat fleet continued, however, to operate actively and effectively in areas, such as the waters off Trinidad, where the traffic was relatively large and the antisubmarine measures relatively weak. | ||

| By the time the AAF Antisubmarine Command was activated, two things had become clear about the submarine war. One was that the Germans would, if at all possible, avoid areas provided with adequate antisubmarine forces. The other was that the most flexible and among the most powerful of those forces consisted of long-range bombardment aircraft, specially equipped and manned for the purpose of hunting and killing submarines. Though dictated primarily by the necessity of destroying as much Allied shipping as possible and preventing the Allies from implementing any logistical plan of major importance. German strategy in the Atlantic always remained sensitive to the | ||

88 |

||

| state of Allied antisubmarine forces, especially air forces. Throughout the antisubmarine war, wherever adequate air cover was provided the submarine withdrew, it tactically possible. In the region of the British Isles, when the same submarine was sighted an average of six times a month it left the area, and when sighted an average of three times a month in American coastal waters it left them. As for the relative effectiveness of aircraft compared to surface vessels. Dr. Bowles, in March 1943, estimated aircraft to be about 10 times as effective in finding submarines as surface craft and at least as effective in killing them.2 | ||

| The U-boat fleet, although strategically on the defensive, had still ample opportunity to operate effectively. The RAF Coastal Command and the Royal Navy had made the British waters unprofitable for it, and had seriously interfered with its free access to the submarine bases on the European coast. The AAF and U. S. Navy had cleared American waters as far south as the Caribbean. But the convoy routes, especially those in the North Atlantic, which bore the weight of Allied strategic supplies, remained relatively unprotected. For air cover, in the absence of adequate very-long-range equipment, it could only protect an area a few hundred miles offshore. This left a large gap in mid-ocean without cover, and as yet the Allies did not have enough strength in carrier escort vessels to provide air cover for this area. Moreover, the Atlantic U-boat fleet was believed to be increasing rather than otherwise. Probably not more than 15 to | ||

89 |

||

| 22 enemy submarines were operating in the Atlantic at the beginning of 1942. At the end of the year this force had risen to about 108, and the Germans were believed to be producing submarines at the rate of between 20 and 25 per month.3 | ||

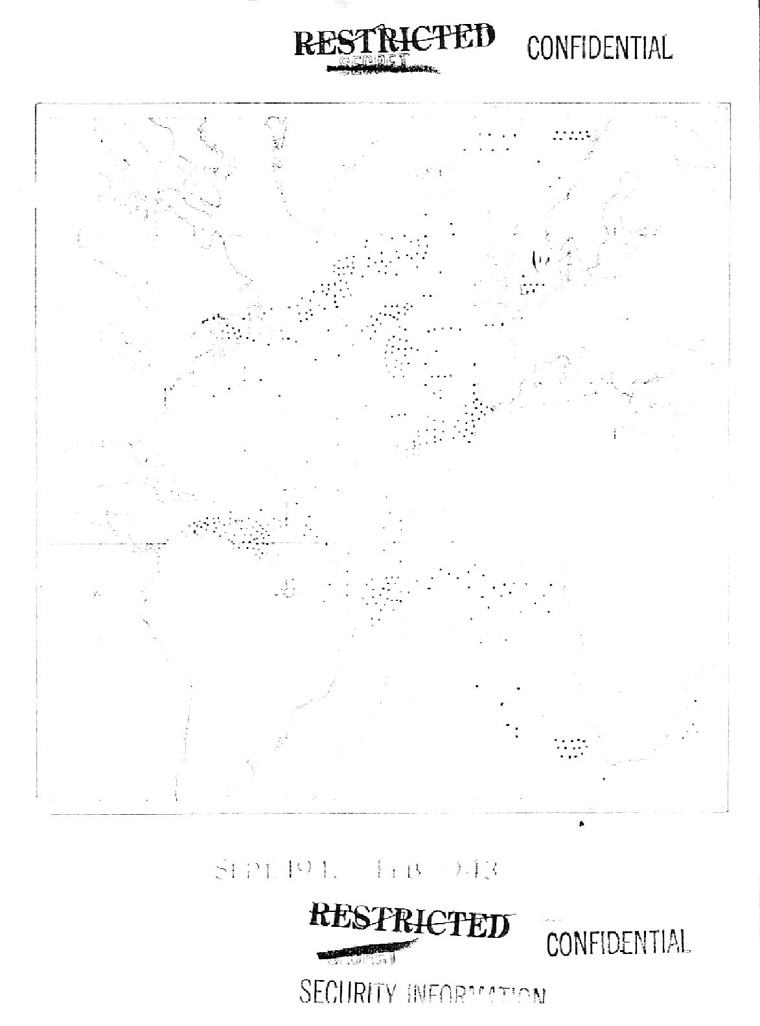

| After a highly successful month in November 1942, the Germans spent a relatively unprofitable winter. Their strategy was apparently to throw out mid-ocean screens in a primarily defensive plan to destroy Allied convoys. It may have been owing to this thinly deployed screen of submarines, extending from 56° north latitude to slightly south of the equator and through which convoys could frequently pass without detection, that few merchant vessels were lost that winter. It may also have been true that the Germans were conserving their forces for a total spring offensive. At any rate, toward the end of February and during the early days of March 1943, it became evident that they were adopting a new strategy involving a concentration of U-boats along the North Atlantic convoy routes. Concurrently with this shifting of forces, the enemy also planned to hold large forces of Allied antisubmarine aircraft and escort vessels in widely scattered control areas. This they could do without too much expenditure of submarines simply by sending small groups into the Eastern, Gulf and Caribbean Sea Frontiers and the Brazilian, Freetown, and Mozambique areas. | ||

| The disposition of enemy forces in the North Atlantic followed a general pattern somewhat as follows. Two roughly parallel screens running in a northwesterly direction were thrown across the convoy routes in such a way as to make contact with both eastbound and westbound | ||

90 |

||

| convoys. As soon as convoys were attacked, the lines would break formation and gather around the the convoy, resuming the parallel screen formation when all feasible measures had been taken to harass the Allied ships. This strategy worked well and accounted for most of the sinkings in the Atlantic, which rose once again to a dangerous total in March. In that month, too, the Allied nations immediately concerned in the Battle of the Atlantic took action to close the gap in their North Atlantic defences. The Atlantic Convoy Conference met, and plans were laid to employ effective long-range air forces in Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland. | ||

| The battle of the North Atlantic reached its climax in early May with the attack on a convoy known as ONS-5. Frustrated by increasingly effective surface escort and air patrol, the Germans threw a large force of submarines into a running battle in a reckless attempt to retrieve some kind of victory from their swindling spring offensive. So reckless was their attack that they lost heavily, and were forced to admit the failure of their attempt to close off the North Atlantic routes. In addition to an increasing number of air attacks of better quality than ever before, the Germans owed their defeat to the introduction by the Allies of aircraft carriers which were able to provide air coverage in any part of the ocean. Planned aerial escort of convoys by carrier-based aircraft had been inaugurated in March. | ||

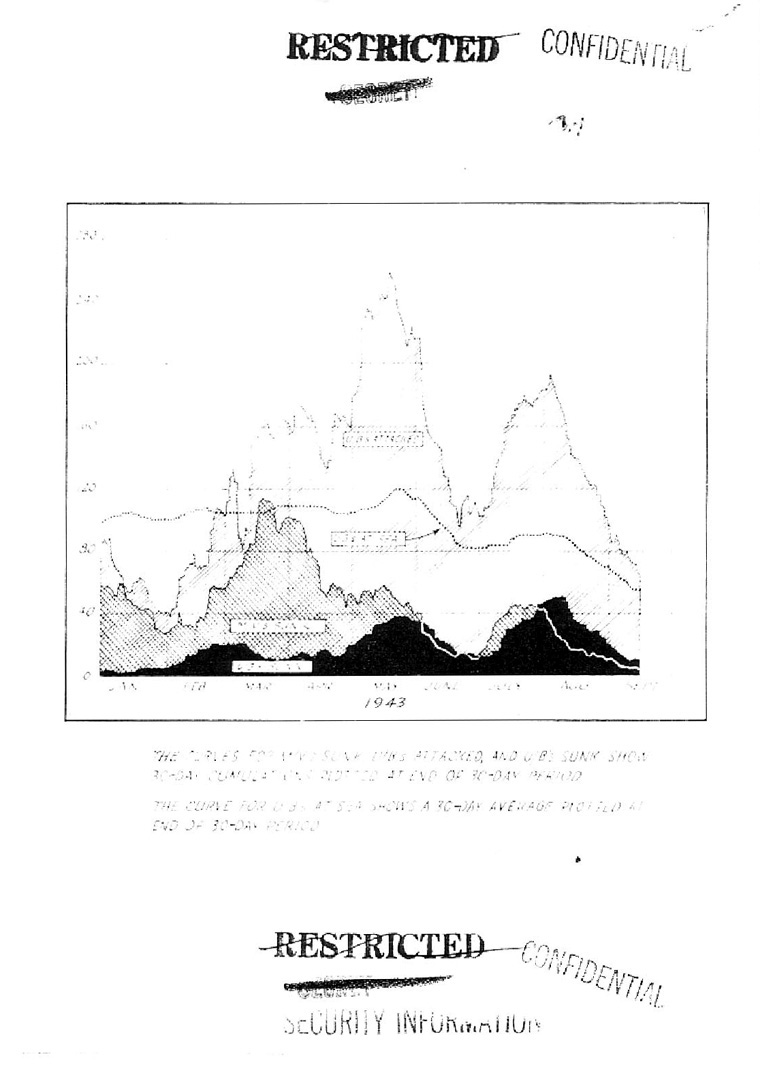

| By early July the enemy had almost abandoned the North Atlantic and the vital war convoys could proceed unmolested. The estimated average daily density of U-boats in the area declined from 58 in May to 16 in June and only 5 in July. Ship losses decreased | ||

91 |

||

| correspondingly from a peak of 38 in March to 14 in May and none in July, despite the fact that nearly 1,700 ship crossings were accomplished in June and July.4 | ||

| Meanwhile, since October 1942, AAF bombers of the Eighth Air Force had joined RAF forces in bombing attacks on German submarine bases, construction yards, and parts plants. This action did little to reduce the number of U-boats at sea nor did it do as much as had been expected to retard the output of submarines, the estimated number of completions by early 1944 having been reduced by not more than 30.5 Meanwhile, also, the RAF with the brief help of two AAF Antisubmarine Command Squadrons, was pressing an offensive campaign in the Bay of Biscay transit area. And both aircraft and surface forces engaged in the antisubmarine war were gradually increasing in effectiveness, as a result of improved weapons and devices, and the increasing experience of their crews. | ||

| It was clear, then, that the Allies, though hampered by lack of unified command, were successfully employing four main methods in their counterattack against the U-boats. First, they were maintaining defensive patrols in coastal areas to hamper and restrict enemy operations. Secondly, they were employing defensive convoy escort and offensive sweeps around convoys in order to prevent the submarine packs from closing in for the attack. Thirdly, offensive bombing missions were being pressed against U-boat bases and building yards. Finally, screens of surface craft and aircraft were being thrown in a continuous offensive action across areas in which U-boats were forced to concentrate. | ||

92 |

||

| A corollary to the increasingly effective antisubmarine campaign may be found in the increasing tendency of the U-boats to fight back. Prior to the spring of 1943, the standard practice on the part of U-boat commanders was to employ a passive defense against air attack and simply to dive on the approach of an enemy plane. If too many planes were encountered, however, a new problem arose. The submarine could not remain submerged indefinitely nor could it make the speed necessary for successful attacks while under water. The decision to employ an active defense came therefore as an admission of the effectiveness of air patrol. It also, of course, gave the attacking aircraft a substantial target for its depth bombs. During July of 1943 these defensive tactics, apparently adopted throughout the U-boat fleet, served to intensify the speed of the submarine war. | ||

| Especially vigorous was the action in the eastern Atlantic. It had been anticipated that the enemy, driven from the North Atlantic convoy routes, would move his forces south to the convoy routes between the United States and the Mediterranean. The latter lanes were not only carrying a substantial and steadily increasing amount of vital traffic in support of the North African and Sicilian campaigns, but, owing to lack of antisubmarine bases in the Azores, much of the route was out of range of land-based aircraft. This anticipation proved entirely correct, for the Germans formed heavy U-boat concentrations south and southwest of the Azores. These submarines enjoyed surprisingly little success. Several factors may have reduced the effectiveness of their groups. Convoys could be | ||

|

|||

93 |

||

| widely dispersed in the wide expanse of the mid-Atlantic; heavy escort was provided, especially for the high-speed troop convoys; and the small aircraft carriers operated effectively in this area. | ||

| Certainly another factor was the action of British and AAF Antisubmarine Command aircraft in the Bay of Biscay transit area and in the approaches to Gibraltar. AAF Antisubmarine Command squadrons were sent in July to reinforce the British offensive in the Bay of Biscay and long-range patrol of the approaches to Gibraltar had been increased in March by the transfer to Northwest Africa of two AAF Antisubmarine Command squadrons from the United Kingdom. In June and July these areas saw some of the sharpest action of the Atlantic war in operations which frustrated any further attempt on the part of the enemy to reorganize a concentrated offensive. During these operations, the Germans threw large forces of medium and heavy aircraft into defensive attacks on antisubmarine aircraft. | ||

| September saw a sadly reduced, if still potentially dangerous submarine fleet being employed by the Germans in the Atlantic. The Germans had deployed an average of about 108 U-boats in the Atlantic during the first five months of 1943. In contrast to these figures, probably not more than 50 were operating in the Atlantic by early September.6 Moreover, the U-boats were now being manned by relatively inexperienced crews, since probably 7,000 trained crew members and officers had been lost in the submarines, estimated at upwards of 150, either sunk or probably sunk during the previous 8 months.7 Most encouraging of all was the fact that from July to | ||

94 |

||

| September 1943 only one-half of 1 per cent of U. S. supplies shipped in the Atlantic were lost through submarine attack.8 | ||

| In accomplishing this great change in U-boat warfare, which until the end of 1943 had run entirely in favor of the enemy, air craft played a major role. By July 1943, aircraft were making 80 to 70 percent of all attacks on U-boats and by the end of the year it was estimated that about 70 percent of the submarines being sunk were lost to aircraft, either land-based or carrier-based. The answer to the U-boat menace had been found to an overwhelming degree in action at sea, and by air attack in particular.9 | ||

| This, in rough outline, was the pattern of events in which the AAF Antisubmarine Command found a not inconspicuous place. | ||

Operations in the Eastern Atlantic |

||

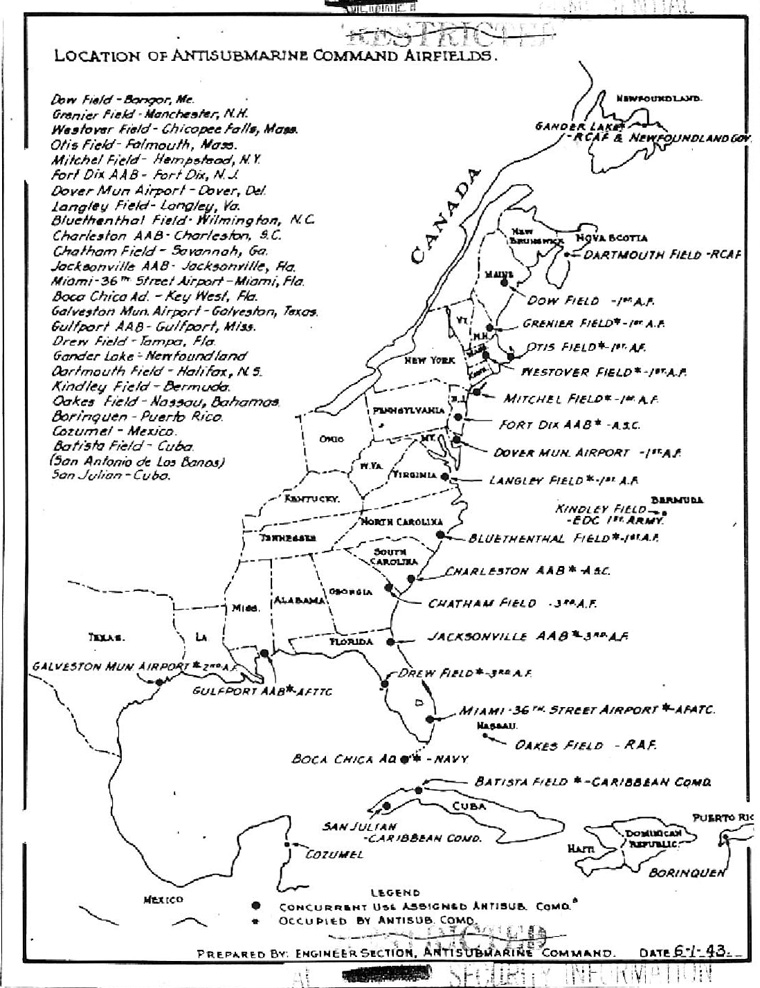

| The Bay of Biscay. The summer of 1942 had left the Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers almost free from the undersurface raiders. While the bulk of the Antisubmarine Command's operational squadrons were engaged in defensive convoy coverage or in the patrol of these uninfested waters, a few units were being allowed to test the command's doctrine of the strategic offensive, and to hunt the U-boats where they abounded, either in their home waters or where they were forced by strategic necessity to be. In November 1942, one squadron of B-24's, equipped with SCR-517C Radar, was sent to England. In January another joined it. During the course of its career, the command sent, in all, six VLR squadrons to operate in the Eastern Atlantic. These | ||

95 |

||

| units, ultimately organized into the 479th and 480th Antisubmarine Groups, contributed the most significant chapter in the AAFAC operational history. | ||

| Probably the most interesting aspect of these eastern Atlantic operations was the participation by the American squadrons in the Bay of Biscay offensive being conducted almost continuously by the British Coastal Command during the period covered by this study. Their participation was of brief duration, but the results were extremely instructive to students of antisubmarine warfare and destructive to the enemy. | ||

| The "Bay offensive" had, by 1943, become the pivotal point for the entire British antisubmarine effort. The strategic theory behind it was very logical. It was well known that most of the U-boats operating in the Atlantic, estimated at upwards of 100.10 were based on ports on the western coast of France. In order to leave these ports for operations against Atlantic shipping and to return for necessary periodic repair and servicing, practically the entire German submarine fleet had to pass through the Bay of Biscay, thus producing a constantly high concentration in the Bay and its approaches.11 Moreover, in crossing this transit area, the U-boats were obliged to spend an appreciable portion of their time on the surface in order to recharge their batteries. It soon occurred to the Coastal Command that the judicious use of a moderate air force in this area would be enough eventually to cripple the U-boat offensive.12 | ||

96 |

||

| Throughout the first 6 months of 1942 the Coastal Command flew a small but steadily increasing number of hours in the Biscay transit area. During the next year, the flying effort in that area was maintained at a relatively high level, averaging between 3,000 and 4,000 hours per month.13 The chief problems to be overcome were lack of very-long-range aircraft capable of covering the entire transit area from English bases, lack of a "balanced" antisubmarine force capable of attacking both day and night, thus making it just as dangerous for U-boats to surface by night as by day, and lack of radar equipment of a kind the Germans could not detect. Early in 1943 a plan was being drawn up, based on comprehensive theoretical studies, calling for an increased and better-balanced flying effort in the Bay of Biscay. An area was determined in the approaches to the Bay, of such a size that every U-boat in transit must surface at least once to recharge its batteries. The expected density of surfaced U-boats in the area was then calculated. It was estimated that a certain number of sorties by specially equipped planes would be required, by day and night, to insure that every submarine in transit would be subjected to attack. It was planned to make extensive use of Mark III radar, which the Germans were apparently unable to detect, in conjunction with the Leigh searchlight in order to make night operations effective. It was claimed that a force of 260 suitably equipped aircraft could account for about 25 U-boats killed and 34 damaged per month.14 Even a force of about 40 long-range aircraft was considered enough to make the enemy abandon the Bay ports, because the U-boats in transit had no retreat from a well-equipped air force. | ||

97 |

||

| And to abandon the Bay ports would mean defeat in the Atlantic, for the Germans could not use Norwegian ports without risking a similarly concentrated offensive in a similar transit area off Scotland and Ireland.15 | ||

| The question had arisen whether this air force would be used to better advantage in a defensive-offensive campaign in the area where the U-boats actually operated. But it was decided that, inasmuch as the Bay offensive, if pressed constantly, would lead to a breaking point, and therefore to total defeat of the U-boats in the Atlantic, it should have priority over the necessarily defensive campaign against the enemy in his operational area. In the open sea the U-boat could choose its time and place, surface or submerge, more nearly at will than was possible in the vital transit area. On the ground of morale alone it was believed the Bay offensive could do irreparable damage to the U-boat fleet.16 | ||

| This was the strategic situation into which the 1st and 2nd AAF Antisubmarine Squadrons were projected in February of 1943. They had been dispatched to the United Kingdom originally for the purpose of training in Coastal Command methods. When thoroughly indoctrinated, they were to proceed to North Africa for action with the Twelfth Air Force.17 While in England, however, plans were altered somewhat. The British were at this point (early 1943) in serious need of long-range antisubmarine aircraft. Though their operations in the Bay had been successful, it was believed that the U-boats were able to remain submerged long enough, with possible brief night | ||

98 |

||

| surfacing, to carry them beyond the outer limit of the British medium-range planes. It was therefore decided to use the two American squadrons of B-24's to supplement the few available long-range British aircraft in a thorough patrol of the outer area, far to the west. The medium-range equipment would then be concentrated in the inner area. These areas were called Outer and Inner Gondola, respectively.13 In view of the then chronic shortage of aircraft, the sustained effort of this Gondola operation was planned to continue for only 9 days, and was dated to coincide with an estimated inrush of U-boats coming away from two convoy battles then in full conflict. The period was actually 6 to 15 February 1943. The results confirmed the wisdom of the plan. Fourteen sightings resulted in nine attacks in Outer Gondola. Only four sightings and one attack came from the inner area. Of the enemy contacts made in the outer area, 90 per cent were by the U. S. aircraft. Thus, Air Marshal Slessor, Air-Officer-Commanding-in-Chief, wrote, some months later. "The two U. S. squadrons . . . played the major part and incidentally 'bloodied themselves in' most successfully in the Anti-U/boat War on this side of the Atlantic."19 | ||

| This is all somewhat ahead of the story. And the Gondola offensive is really only part of the story. It was no simple task to transplant two American squadrons and train them under foreign conditions to such a point that they could turn in a record such as that outlined above. Many U. S. bombardment squadrons had preceded them to England and as components of the Eighth Air Force had become successfully operational. But they had from the beginning formed | ||

99 |

||

| part of a well-organized and sizeable American force, and had pioneered in an entirely different type of warfare from that to which the 1st and 2nd Antisubmarine Squadrons were committed. The latter units, in fact, found the way but poorly prepared for them in the United Kingdom.20 | ||

| To begin with, on its arrival at St. Eval on 7 November 1942, the advance units of the 1st Antisubmarine Squadron found that no one knew anything of the plans for it. The decision to send it and the 2nd Antisubmarine Squadron had been made in haste and in great secrecy, and it took the commanding officer, Lt. Col. Jack Roberts, some time to find out where his unit should operate and under whose control. After a series of conversations with the Commanding General of the Eighth Air Force, it was finally settled that the squadron should be attached to the VIII Bomber Command for supply and administration, and that it should remain at St. Eval under the operational control of the RAF Coastal Command. When the 2nd Antisubmarine Squadron arrived in January 1943, it was stationed at the same field and placed under the same administrative control.21 On 15 January 1943 the two squadrons were combined in the 1st Antisubmarine Group (Prov.), under the command of Colonel Roberts, working as a detached unit of the 25th Antisubmarine Wing of the Antisubmarine Command.22 | ||

| It had been understood prior to departure from the United States that maintenance for aircraft would be provided immediately after arrival. Actually, there were no adequate facilities or personnel | ||

100 |

||

| for this purpose. The VII Bomber Command quickly detached 65 mechanics, ordnance men, armament specialists, and guards, but the men were not experienced in B-24 aircraft at that time, and they joined the group reluctantly since it meant leaving their own promotion lists. It proved to be a considerable problem to weld these men into an efficient maintenance team, but one that was fortunately soon solved.23 | ||

| St. Eval was already overcrowded with squadrons of the Coastal Command. No hangar space was available for maintenance. The result was that all such work had to be done during the limited number of daylight hours in the open, the mechanics unprotected from the raw weather of a British winter. Nearly 50 per cent of the personnel immediately contracted heavy bronchial colds, a situation which presented a real problem to the flight surgeon who lacked even the simplest medicines. Furthermore, there were no quarters available for the officers and men at the station, so it was necessary to scatter them at considerable distances from the field. For quite a while, too, the American units had to eat British rations, since no separate mess facilities had been provided.24 | ||

| St. Eval was far removed from any established Services of Supply or Air Service Command supply depots, finance offices, or Army post offices, nor had any adequate communications or supply channels been set up to reach it. As a result, the nearest depots were at first a difficult day's drive away. Later, a newly established depot was located that could be reached by a 5-hour drive.25 | ||

101 |

||

| In addition to these initial difficulties, there were several serious administrative and operational problems which could scarcely have been solved until the units were in the theatre. The squadrons had been sent to England with no idea of prolonged operations in that area. They, therefore, found themselves short of personnel, a situation which was not improved by generally prevalent illness. Officer personnel was especially overtaxed.26 Moreover, since the group was at that time provisional, the commanding officer found himself without adequate authority in some respects. For example, he could neither promote deserving personnel nor demote a few recalcitrant individuals -- in either case a condition detrimental to group morale.27 The squadrons were immediately faced with innumerable problems in learning British control methods, navigational aids, communications, and other procedures. Even some British customs provided minor but troublesome problems. British military custom, for instance, draws a sharp line of demarcation among enlisted men between sergeants and those of lower rank, and provides each group with its own housing and recreational facilities. The American crews had to be similarly divided although such division was contrary to U. S. Army custom.28 | ||

| Some difficulty arose over the nature of the "operational control" to be exercised by the Coastal Command. As in the case of the U. S. Navy's control, the term had not been clearly defined. Questions at once arose. Did operational control mean that missions could be ordered if weather conditions were, in the opinion of the group commander, too hazardous? Would he have a voice in determining | ||

102 |

||

| assignments?29 These and similar questions carried serious potentialities which could easily have wrecked current and future cooperation between Allied commands.30 Officers of the group had, however, nothing but praise for the cooperation they received from the RAF Coastal Command. That organization gave freely of its long experience in antisubmarine warfare, a contribution which proved invaluable in guiding and training the novice squadrons. It left to the group commander final decision on all assignments as well as on all questions of recall or diversion of missions, whether owing to weather or enemy activity. The Army Air Forces Controller, who worked directly with the British Controller, had the full privilege of handling all control of American aircraft if in his judgment intervention was advisable. British radio communications proved to be excellent and the British control officers soon gained the complete confidence of all flying personnel. The British spared no effort in guiding aircraft to safe bases, regardless of risks involved, and fields were always fully lighted for landing despite the constant and often immediate threat of attack from enemy aircraft operating from bases only 100 miles distant.31 | ||

| The 1st Antisubmarine Squadron flew its first mission in European waters on 16 November 1942, just 9 days after its arrival in the United Kingdom. Operations continued rather slowly for a while, since at first only three planes were available. Additional aircraft became operational during the following 90 days. Exactly 2 months later, on 16 January 1943, the 2nd Antisubmarine Squadron | ||

102a |

||

| flew its first mission. These small initial operations provided invaluable experience, for they demonstrated the operational problems that were to face all U. S. squadrons in European areas and they served as laboratory tests that proved the amount and type of additional training needed for newly arrived units. 32 | ||

| The job of training to meet the conditions of operation in the eastern Atlantic, and under the control of the British, was a large one. Much instruction had to be given in the use of British depth bombs, in the British methods of diverting aircraft to alternate fields when weather proved suddenly adverse, and in British control and radio procedures which differed substantially from American. Recognition of enemy and friendly aircraft had to be exact in an area covered by enemy as well as by friendly patrols. Enemy capabilities, tactics, and methods of combat had to be learned. Extra training in navigation was especially important since many of the navigational aids to which U. S. navigators were accustomed, such as radio beams, could not be used in the ETO; and even a small navigational error in returning from a 2,000-mile sea mission might put the aircraft over enemy territory.33 | ||

| As for equipment, the new SCR-517C radar proved the principal problem. The aircraft of the squadrons had been equipped with this latest device immediately prior to leaving the United States. A supply of spare parts was lost en route, the equipment had not been "shaken down" before departure, the radar operators in the organization had not been trained in its use, and experienced mechanics could not | ||

103 |

||

| be found in the United Kingdom. Once these initial difficulties had been surmounted, the radar sets proved their worth, accounting for many sightings that probably could not have been made with British equipment.34 The B-24 aircraft themselves gave very little trouble. The only serious difficulty arose in adapting them to carry 10 to 12 of the British Torpex 250-pound depth bombs without shifting forward the center of gravity of the airplane.35 | ||

| The chain of command in the Coastal Command was similar to that in the AAF Antisubmarine Command. The 1st Provisional Group operated under the Station Commander, St. Eval, who received his orders from Headquarters, 19 Group, RAF, which corresponded to the wing organization in the AAF Antisubmarine Command. The squadrons reported daily to the Station Controller the number of planes and crews available for missions the following day. The Controller then assigned take-off times. Crews reported for briefing 2 hours prior to scheduled take-off and received lunches, pyrotechnics, and all other equipment and information relative to the mission.36 Operational missions generally were of 11 to 14 hours' duration in order to make full use of the long-range potentialities of the B-24. Such long missions, searching far out over the ocean, proved exceedingly fatiguing to the combat crews, especially when executed under adverse weather conditions. When it is considered that these squadrons arrived in the United Kingdom at the beginning of the worst months normally experienced in a country not noted for its fine winter climate, it can readily be seen that the long-distance patrols were only for tough and young | ||

104 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| men.37 Missions at first were planned every third day, but it was found that, in the interests of the mental and physical health of the men, 3 days would have to elapse between missions.38 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The following table indicated the extent of operations of the group from the United Kingdom:39 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In view of the fact that few aircraft were available during November and December 1942, and that the 2nd Antisubmarine Squadron did not fly its first operational mission until 16 January 1943, the record of nearly 2,000 hours of operational flying during the months of worst British weather is highly satisfactory. The record of sightings and attacks is also good. On the average, 1 sighting was made for every 98.3 hours of flying time, and i attack for each 177.4 hours of flight, a record far more satisfying than that being achieved during the same period on the U. S. Atlantic coast where the scarcity of U-boats necessitated many thousands of hours of flying for each sighting.40 Most striking of all, however, are the figures for the Gondola campaign in early February. This action proved to be the climax of the operations of the 1st Provisional Group (later the 480th Group) during its stay in the United Kingdom. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

105 |

||

| On 20 occasions, aircraft of the group, while flying from the United Kingdom, sighted enemy U-boats. In 11 instances attacks followed. In the remaining 9, the U-boat had been submerged so long before the arrival of the attacking aircraft that no depth bombs were released, a procedure quite in accordance with instructions. In these early months of operation a great deal of difficulty was experienced in adjusting release mechanisms to function properly with the British type of depth bomb. In 3 out of 11 attacks made, the depth bombs "hung up" and so frustrated what might otherwise have been excellent attacks. Of the 8 attacks not thwarted by mechanical failure, the assessed results were:41 | ||

| 1 probably sunk | ||

| 1 so severely damaged that it probably failed to reach port | ||

| 1 severely damaged | ||

| 3 insufficient evidence of damage | ||

| 2 no damage | ||

| The aircraft of the group did not conduct these early operations unopposed. For many months Allied aircraft had been free to fly over the Bay without opposition from enemy planes, but, as the Allied air patrols increased and crossing the Bay became correspondingly more difficult, the enemy began to put medium-range twin-engine fighters over the area in increasing numbers. This tendency was becoming apparent during the period when the 480th Group operated from the United Kingdom. Some months later, the 479th Group encountered much greater opposition from the JU-88's. During the winter months, aircraft of the 480th Group engaged enemy planes on four occasions. As | ||

106 |

||

| a result, two JU-88's were at least damaged and quite possibly destroyed. They were last seen losing altitude rapidly and smoking heavily. On another occasion one of the group was known to have engaged in aerial combat but failed to return to its base or render any report by radio. Two other aircraft failed to return to their base, but no indication remains as to the cause of their loss.42 | ||

| The successful operations of the 480th Antisubmarine Group from St. Eval were not accomplished without cost in lives and aircraft. In all, 65 officers and men lost their lives, and 7 B-24's were destroyed. Of the latter, 2 were lost in crossing the Atlantic to England, 2 failed to return from a mission, their fate unknown, 2 crashed, and the seventh was doubtless destroyed in aerial combat.43 | ||

| In March 1943 the 480th Group was ordered to Port Lyautey, French Morocco, to engage in antisubmarine patrol of the vital approaches to the TORCH area. The final mission from the United Kingdom were flown on 5 March. In 6 weeks of full operations and during the preceding 2 months of limited operations, the 480th Group had made a very solid contribution to the antisubmarine effort in the eastern Atlantic. Of the 49 sightings and 26 attacks made during the critical month of February by all units operating on antisubmarine duty from the United Kingdom and Iceland, the 1st and 2nd Antisubmarine Squadrons alone accounted for 15 sightings and 5 completed attacks. Even more important was the pioneering work done in foreign operations, a contribution which led to the solution of many troublesome administrative and technical problems. Their withdrawal was noted by the British Coastal Command "with keen regret."44 | ||

107 |

||

| The campaign of early February in the Gondola area had demonstrated the feasibility of a sustained and concentrated air offensive in the Bay of Biscay. After the departure of the 480th Antisubmarine Group, the Coastal Command continued to hit the U-boats in transit as heavily as its resources would permit.45 The British also agitated with increasing insistence for an Allied offensive, launched on an unprecedented scale, in the Bay area. In March it was proposed by the British that a combined British and American contribution of 160 additional VLR, ASV-equipped aircraft and crews to be organized to be added to the force of 100 aircraft then said to be devoted by the Coastal Command to the Bay patrol. This force would constitute the tactical elements of a specially staffed British and American organization to be assigned the specific mission of offensive air operations in the approaches to the Bay of Biscay during the period May to August, inclusive.46 The plan, involving as it did the creation of a distinct task force, separate in organization, did not coincide with AAF plans which conceived the Bay project as but one aspect of a single air task of much broader scope, namely, the protection of the Atlantic lines of communication against submarine attack. Furthermore, it was pretty obvious that any implementing of the Bay of Biscay plan would have to be done by the AAF at the expense of ETO heavy-bombing operations, for the U. S. Navy was not planning to do more than add 45 planes to those already engaged in North Atlantic antisubmarine activity.47 The AAF was both unwilling to compromise its current commitments of heavy bombers and crews to the Eighth Air Force and | ||

108 |

||

| reluctant to incur further commitments with regard to the Atlantic antisubmarine campaign until it could be finally determined what organization would ultimately be responsible for U. S. air operations against submarines in the Atlantic.48 The British authorities felt strongly that the Bay offensive would do more than any other single factor to end the "present unsatisfactory progress in the Battle of the Atlantic." And time, in this instance, was at a premium: 3 to 6 months later, the Germans might be shifting their efforts to Norway, threby necessitating an entirely new project, and one less feasible than that proposed in the Bay of Biscay.49 | ||

| Support for this view came from an unexpected source. The U. S. Navy, which had been hitherto officially against the use of antisubmarine forces in a purely offensive campaign, came, in June 1943, to favor the plan and urge its adoption. Admiral King, early in June, had suggested that two Army VLR squadrons be sent from Newfoundland to the United Kingdom to participate in the Bay of Biscay project. There were, he pointed out, more VLR aircraft in the Newfoundland area than were set up as a minimum requirement for that area by the Atlantic Convoy Conference (ACC 3).50 Finally, in the latter part of June, the 4th and 19th Antisubmarine Squadrons were ordered from Newfoundland to duty in the United Kingdom. These units became the backbone of the 479th Antisubmarine Group, activated in England in July 1943.51 | ||

| Meanwhile, the British had gone ahead with plans of their own for a concentrated offensive in the Bay and its approaches. The | ||

109 |

||

| losses, which had been inflicted on the U-boats in May, forced the German command to withdraw their fleet from the North Atlantic convoy route and to operate against independent shipping in scattered areas. This shift in enemy strategy forced the British to redouble their efforts in the Bay transit area, for there alone could the enemy be found with any degree of certainty. Accordingly, it was decided in early June to concentrate in the Bay offensive all available aircraft not required for close escort of convoys, and to reinforce these by surface support groups withdrawn from the convoy routes. The resulting joint antisubmarine striking forces were deployed in two new antisubmarine areas in the Bay known as "Musketry" and "Seaslug."52 Reinforcement of the patrol of these areas, especially in their southern reaches, came from the Allied forces in the Moroccan Sea Frontier and at Gibraltar. The newly intensified offensive met with early success. The enemy attempted to counter it by sending their submarines through the bay in close groups of two, three, sometimes even five. This practice, while it concentrated a formidable screen of antiaircraft fire against individually patrolling planes, presented a tempting target for a well-balanced antisubmarine force. On 30 July a whole group of three U-boats was sunk in a combined air and surface action. | ||

| The 479th Group began its work in the United Kingdom with a double advantage in its favor. Not only had the project been less hastily organized than that of the 480th, but it profited from the pioneering work done in the field by the older unit. Upon the | ||

110 |

||

| arrival of its flight echelon at St. Eval (the first 13 airplanes landed there on 30 June, the remaining 11 on 7 July), the group was placed under the Eighth Air Force for administration and supply and under the 19 Group, RAF Coastal Command, for operational control. It was decided not to keep it at St. Eval but to turn over to its use a new field at Dunkeswell, Devonshire. At this field the men of the 479th enjoyed the advantage of a relatively separate establishment, under the control of Col. Howard Moore, commanding officer of the Group, with Group Captain Kidd of the Coastal Command exercising only a general supervision.53 The 87th Service Squadron, 1813th Ordnance Service and Maintenance Company, the 1177th Military Police Company, and the 444th Quartermaster Platoon arrived in England with the group's ground echelon and were attached to it at Dunkeswell. It is not surprising, then, that the 479th escaped some of the more vexing administrative and logistical problems which faced the 480th on its arrival. The men of the 479th even received American rations at this new station.54 The incomplete state of construction at Dunkeswell did, it is true, impose some discomfort on the new occupants. Nevertheless, the group at once settled down to training under the novel conditions of operations in the United Kingdom. The problems met in this regard were much the same as those encountered by the 480th.55 On 13 July aircraft of the 479th Group flew their first operational missions.56 | ||

| Not long afterward (29 July) Air Marshal Slessor spoke of the "most welcome reinforcement" provided by the two squadrons of the | ||

111 |

||

| group "for the 'Muskestry' area where hunting had been quite good this month."57 The 479th had, indeed, taken an extremely active part on the Muskestry campaign. During the 19 days, from 13 July to 8 August, aircraft of the 4th and 19th Squadrons sighted 12 submarines and attacked 7 of them. Of those attacked, 3 are known to have been sunk. 2 with the aid of RAF aircraft patrolling in the vicinity. Enemy tactics thereafter changed. The U-boats abandoned the policy of staying on the surface and fighting the attacking aircraft and henceforth made every effort to avoid surfacing during daylight hours. After a successful attack on 2 August, only 1 additional sighting occurred during the entire remaining period of operation, to 31 October; and even this sighting did not result in a successful attack.58 | ||

| Most of the attacks (six out of eight) made by the 479th Group were made in the face of determined countermeasures on the part of U-boat crews. In a desperate attempt to nullify the air offensive that was bidding fair to strangle their submarine fleet, the enemy had resorted to the policy, ultimately disastrous to itself, of remaining surfaced during an attack and fighting back with antiaircraft fire. One B-24 was believed lost as a result of this action.59 | ||

| Much more serious was the opposition encountered from enemy aircraft, though just as indicative of the enemy's desperate plight. German aircraft over the Bay in July and August accounted for 2 aircraft and 14 lives. JU-88's were encountered throughout the entire period of operations, often in very large groups. The average number | ||

112 |

||

| was 6.6 enemy aircraft per encounter. It is therefore cause for surprise that so few planes of the 479th were lost. Even so, of course, the strain on the crews of the single B-24's in the face of such large groups was very great. Crews were instructed to avoid combat whenever possible, but in many instances the enemy pressed the attack vigorously. For a tabulation of the results of these encounters, in which the antagonists may be said to have fought to a draw, the reader should consult Appendix 3.60 | ||

| It is not the province of this study to evaluate the entire Biscay offensive. It continued long after the AAF Antisubmarine Command had ceased to exist, and until the submarine menace itself had been substantially reduced. But some assessment must be attempted, at least for the period during which AAF Antisubmarine squadrons participated. It has been suggested that the campaign was a failure.61 Certainly the tangible results obtained in August failed to measure up to those of July. In July, 26 percent of all attacks made on U-boats were made in the Bay, and the B-24's of the Antisubmarine Command operating in that area had to fly on average of only 54 flying hours per sighting. The situation altered radically in August. Only seven damaging or destructive attacks were made in that month, as compared to 29 for July. Sightings fell off proportionally, and the 479th Antisubmarine Group certainly spent most of its time in August combating enemy aircraft rather than in attacking U-boats. Yet throughout the month of August, plotting boards regularly carried from 10 to 20 U-boats in the area, which is approximately the same | ||

113 |

||

| concentration as characterized the previous month. Nor can the decrease be charged to any relaxation of the offensive effort. | ||

| The failure to sight the enemy in August may be explained in part as the result of the installation of radar by the Germans in their submarines. Increasingly, the aircraft on antisubmarine patrol found that the "blips" disappeared from the radar screens at average distances of 8 or 9 miles, indicating that the enemy was detecting patrol aircraft at safe distances. The Germans also altered their tactics considerably in order to cut down the heavy losses sustained by them in July. They abandoned the practice of remaining surfaced and fighting back during air attacks, and resorted again to an over-all policy of evasion, hugging the Spanish coastline so as to confuse radar contacts, and surfacing only at night in that farthest south part of the Bay which lay at the extreme limit of the English Wellington's equipped with Leigh-lights. Some credit must also be given to the persistent use of aircraft to counter the pressure of the Allied air offensive.62 | ||

| Nevertheless, it must be remembered that the tactics to which the Germans resorted -- fighting back in July, hugging the Spanish coast in August, and using extremely heavy air cover in both months -- are themselves eloquent evidence of the effectiveness of the Bay offensive. And the effect of antisubmarine activity cannot be determined entirely by the amount of damage directly inflicted on the enemy. The constant patrolling of the Bay forced the submarines to proceed so slowly through the transit area that their efficiency | ||

114 |

|||||||||||

| in the open sea was greatly reduced and the morale of their crews seriously impaired.63 Yet, even in terms of submarines sunk or damaged, the Bay campaign inflicted heavy loss on the enemy. During its most active 3 months (June to September) it accounted for the following score:64 | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

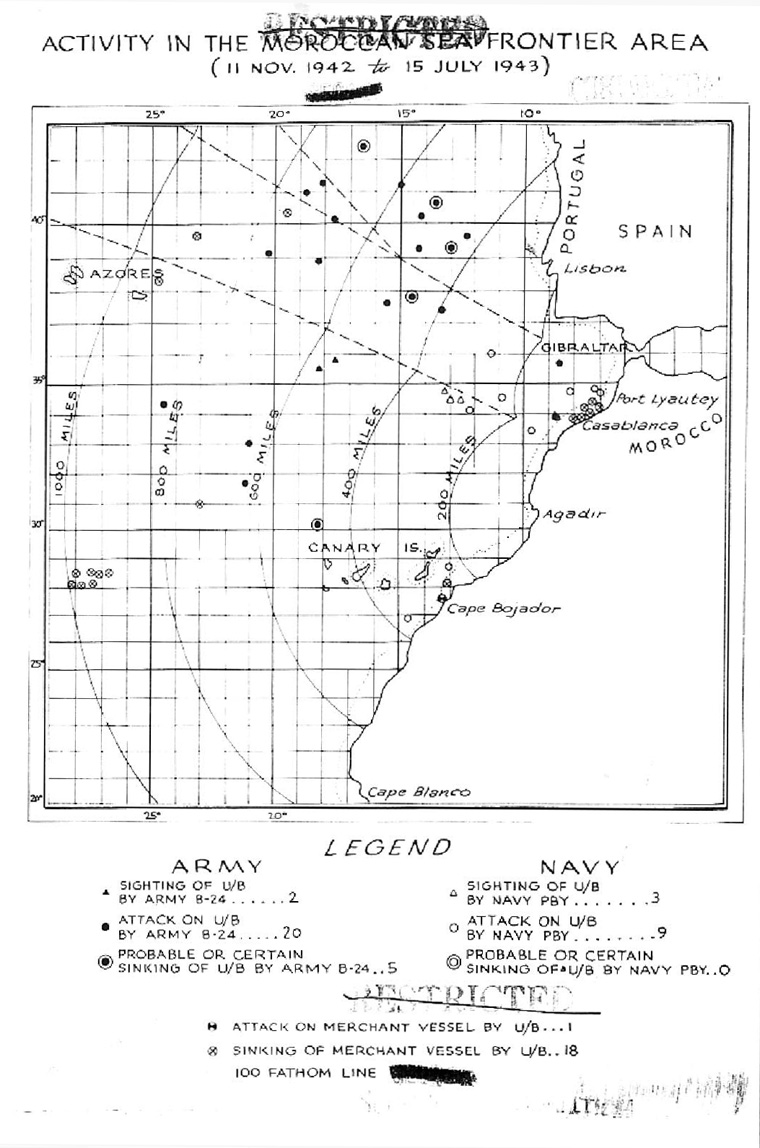

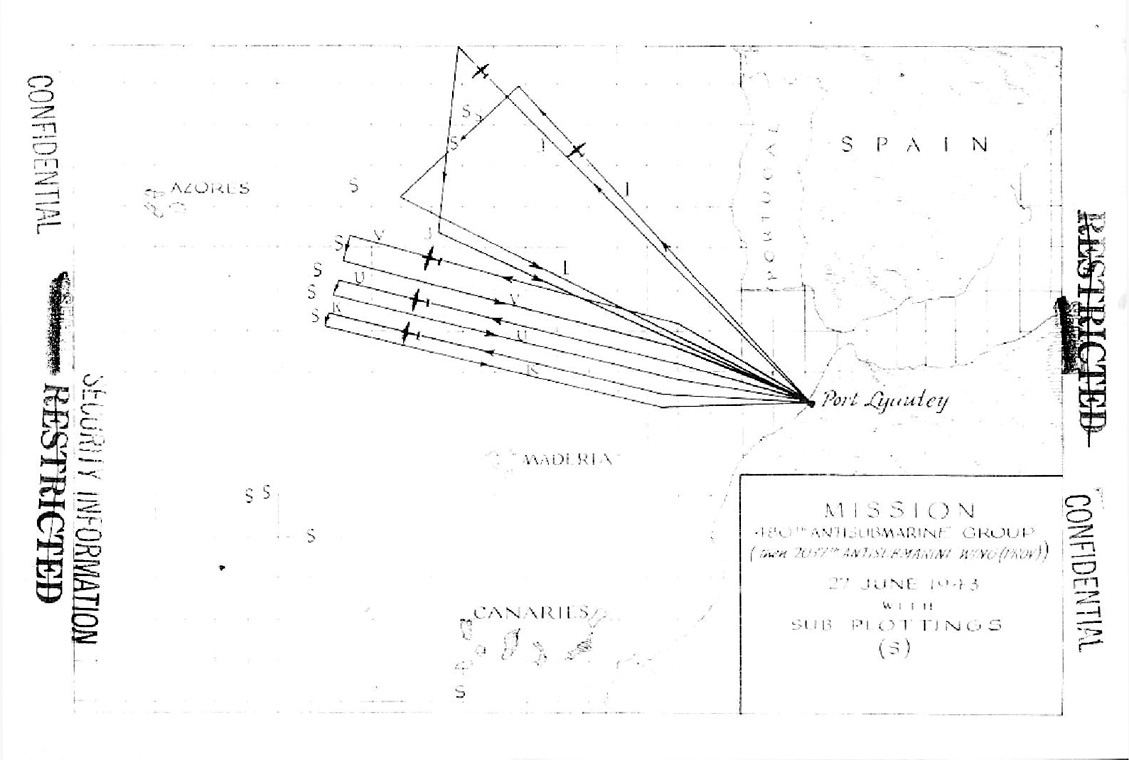

| The Moroccan Sea Frontier. Closely related to the Bay of Biscay offensive was the action in the Moroccan Sea Frontier. In fact, the two at times overlapped, aircraft from the latter reinforcing the campaign in the transit area, at least in its more southerly reaches. In any event, the antisubmarine warfare in the approaches to the Straits of Gibraltar was always likely to be affected by strategy in the Bay, probably even more than other Atlantic areas, all of which were affected in one way or another. As the summer Bay offensive reached its climax in late June and early July, the U-boats tended more and more to skirt the Spanish coast to Cape Finisterre, and from there to deploy in a southwesterly direction toward the waters between the Azores and the coast of Portugal. The result was a concentration, during the first 2 weeks of July, of enemy submarines in that area, which thus became part of the narrow transit lane. | |||||||||||

| It is a matter of question what exactly were the strategic motives back of this movement. Undoubtedly, it sprang in large part | |||||||||||

115 |

||

| simply from a desire to evade patrolling forces in the Bay. But it also appears to be true that the U-boats were spending considerable time in that region on antishipping patrol. It may very well have been that they were ordered to spend several days in these waters on their way to and from their Biscay bases.56 The object was apparently to create a screen off the coast of Portugal to intercept Allied convoys proceeding from the United Kingdom to supply the Allied campaign then being developed in the Mediterranean. It was a bold move, for it brought the U-boats within range of antisubmarine aircraft operating from Northwest Africa and Gibraltar, and it coincided with the brief and desperate attempt of the submarines in the bay to counter the air offensive by antiaircraft fire. The enemy also relied on the relative ease with which air protection could be provided in the form of JU-88's and the longer range FW-200's. There is difference of opinion concerning the precise number of U-boats patrolling off the coast of Portugal in the first half of July, the estimate ranging from 8 to 25. But it is certain that a considerable concentration came within range of African-bases Liberators.67 | ||

| It is at this point that the B-24's of the 480th Group reenter the picture. They had been moved to Port Lyautey in March and had extended the patrolled area in the Moroccan Sea Frontier by several hundred miles. These squadrons were especially equipped to answer the challenge made by the U-boats as the latter swung across the convoy lane in early July. Their offensive really began with a sighting on 6th July in which the pilot made a perfectly executed run | ||

116 |

||

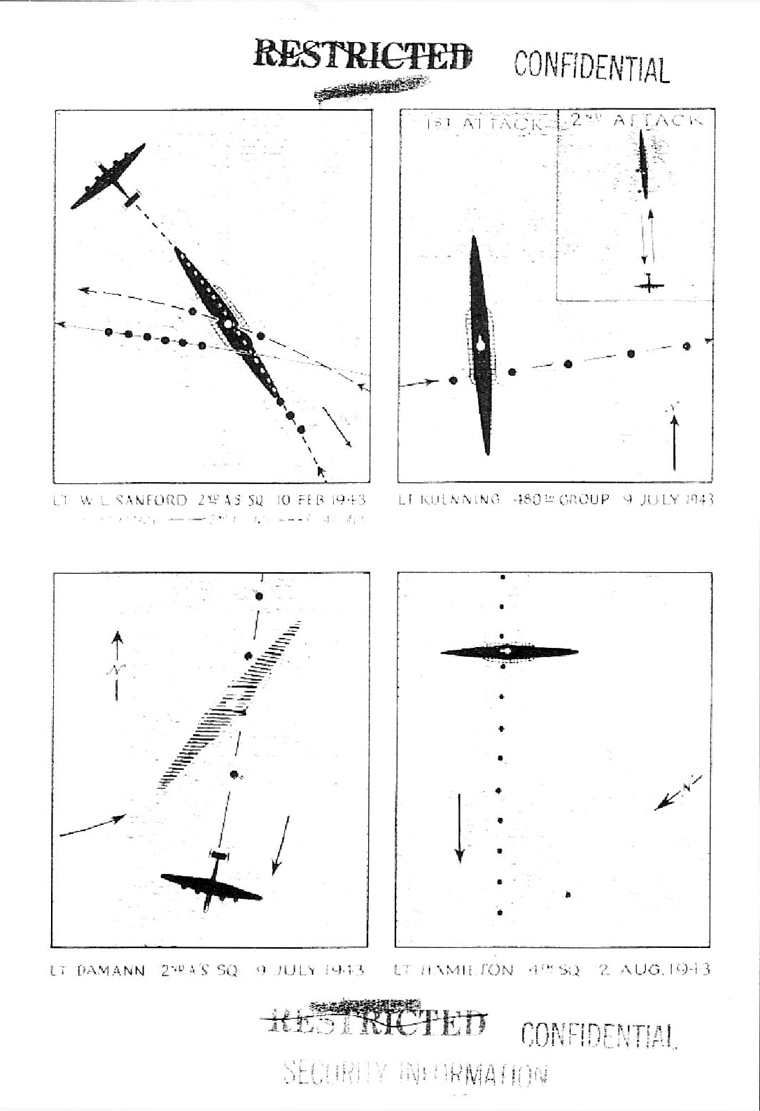

| on a submarine, but was foiled by mechanical failure of his bomb bay doors. On the 7th, two attacks were made, one of which resulted in the probable sinking of one U-boat. The other may also have been destroyed, although it was officially assessed as probably severely damaged. The following day a fifth attack occurred which resulted in another probable kill. On 9 July three attacks were delivered, one of which was assessed as severe damage, one as slight damage, and one as no damage at all. Next day another attack resulted in doubtful damage, and again on the 11th an attack of undetermined effect was executed. On the 12th, 13th, and 14th, an attack was made each day, resulting in one submarine definitely destroyed and two damaged. Thus during this short period of 10 days, the 2 squadrons made 15 sightings and 13 attacks, which are believed to have resulted in 1 submarine known sunk, 3 probably sunk, 2 severely damaged, and 1 possibly damaged. Only 6 attacks were considered unsuccessful.68 | ||

| After this decisive, if local, defeat, the enemy obviously decided to abandon his policy of active defense. The U-boats now dived, whenever possible, on sight of antisubmarine aircraft, and not a single submarine was sighted by AAF aircraft in the area thereafter. It was also immediately after this brief "blitz" that the Germans began to patrol the area with heavy armed FW-200's, and it is logical to presume that the action of the 480th Group had a good deal to do with that development.69 | ||

| In order to put this July offensive in its proper perspective, it will be necessary to review the history of operations in the | ||

117 |

||

| Moroccan Sea Frontier from the time when Col. Jack Roberts and his 480th Antisubmarine Group reported at Port Lyautey in March 1943.70 | ||

| The 480th Group encountered in Africa something more that the usual problems involved in transfer to a new theatre. Most of the difficulties arose from the fact that the group was now placed under the operational control of the U. S. Navy. It was assigned to the Northwest African Coastal Air Force for administration, and attached temporarily to Fleet Air Wing 15 for operational control, pending decision as to the control and disposition of all Allied antisubmarine units in Northwest Africa and Gibraltar.71 Colonel Roberts felt that this arrangement was most unsatisfactory for several reasons. The group had been the first of the AAF Antisubmarine Command units to operate free from U. S. naval control. It had been thoroughly indoctrinated in RAF Coastal Command procedures, which differed markedly from those of the U. S. Navy, and the officers of the group felt that, for the job at hand, they were much superior. Morale was adversely affected by poorer radio communications, less efficient briefing and operational control, poorer air-sea rescue facilities, and RDF than those to which the unit had become accustomed.72 An example of the resulting friction was that, with five intelligence officers capable and experienced in briefing and interrogating crews, the group was not allowed to provide watch in the control room or to conduct briefing. Since the briefing provided by Fleet Air Wing 15 was not considered adequate by Colonel Roberts, crews had to be re-briefed by an officer of the group before going on a mission.73 Worse than that, | ||

118 |

|||

| intelligence data necessary for successful missions frequently got to the group too late to be of any real value. And, with practically no operational authority, there was little that Colonel Roberts could do about it. Nor was much attention being paid to estimated U-boat positions in routing patrol aircraft, which resulted in poorly planned missions. In general, it was felt that the best use was not being made of a highly trained organization.74 | |||

| Basically, the trouble lay in the difference of strategic thinking between Navy and AAF Antisubmarine Command:75 | |||

|

|||

| As will appear in the following pages, the Navy had performed its initial function adequately by patrolling the approaches to Gibraltar to within 400 miles and had helped to force the Germans beyond that limit. But the long-range and very-long range aircraft of the Antisubmarine Command had a new and different mission to perform, namely, that of reaching beyond the 400-mile line and striking the submarines prowling in the outer waters. The two missions thus required two different approaches, a fact which the Moroccan Sea Frontier failed to appreciate. | |||

| Since the problem of command in the Gibraltar-Northwest African area was currently under discussion in the spring of 1943, 76 Colonel | |||

119 |

||

| Roberts vigorously urged, as a solution, placing antisubmarine operations in the area under British control at Gibraltar. The RAF Coastal Command was operating antisubmarine squadrons from both Gibraltar and Agadir -- to the north and south of Port Lyautey respectively. So he believed the best interests of all concerned would be served by coordinating operations from all three bases under Coastal Command control. "I am. . . convinced [he wrote in May], as are all of my subordinates, that our Wing can operate "independently" under the central control of AOC Gibraltar with much greater efficiency and effectiveness than under present U. S. Navy control." This statement, he warned, was made without malice toward any individuals of the Navy "thereabouts," for they were "generally a fine bunch with whom our relations are on a most pleasant basis." He then added, significantly, "The majority of them privately concur with me in my expressed ideas on antisubmarine organization in Northwest Africa."73 | ||

| In fact, by June improvement was becoming evident in the general control exercised by Fleet Air Wing 15, and in the quality of services furnished at Port Lyautey, although no change in the official status of the group, or in the quantity of services, had taken place. Group intelligence officers were being given equal authority and responsibility with naval, and air-ground liaison was "reasonably satisfactory."79 Army and Navy intelligence officers were rotating duty shifts in the Control Room. And the group was exercising increased authority, "actually, if not officially." in the laying out of patrols. "the Navy exhibiting little interest in anything other than convoy coverage."80 | ||

120 |

||

| The Navy did not, of course, furnish all the problems facing the 480th Group in Africa, though it provided the largest of them. In addition to the myriad of problems incident on stationing several hundred men in a strange territory and climate, Colonel Roberts had to build up his unit from a strength of not more than 16 or 17 VLR aircraft to one of 24 VLR (E).81 This increase in aircraft, especially in the modified B-24D, involved considerable training of crews both old and new, and considerable adjustment of equipment.82 As of 23 June 1943, the group reported 19 VLR (E) aircraft on hand, with 6 en route from the United States.83 | ||

| The 480th Group arrived in Africa as a well-trained unit. Thanks to the experience gained under the tutelage of the Coastal Command, the group officers felt that their organization was better prepared for antisubmarine tasks than any other American unit.84 And the quality of the new crews received from the OTU at Langley Field had steadily improved.85 The chief training problem consequently arose in connection with the new equipment being received and the unfamiliar flying conditions prevailing in the Moroccan Sea Frontier, where scarcity of clouds made tactics learned under the heavier northern skies inapplicable.86 The commanding officer was especially conscious of the value of continuous training, and, once such facilities as a triangulation bombing range and a blind-landing system had been set up, he maintained a steady training schedule.87 | ||

| Morale constituted an ever-present, though happily not a serious, problem. At first the crews felt insecure under what they considered | ||

121 |

||

| inferior radio control from the Navy, and in view of the fact that rescue facilities were lacking. Recreation facilities remained limited, relaxation consisting mainly of athletics and an earnest endeavor to consume enough liquor before 2000 to make a pass, normally expiring at that hour, worth the trouble of securing. Unfortunately, the 480th Group was the only "front line" unit in what was considered to be a rear echelon, or rest area, and the Provost Marshal persisted in subjecting it to the same type of restrictions ordinarily imposed in inactive units. Morale in general, however, remained high until, in August, rumors of the impending dissolution of the AAF Antisubmarine Command left all personnel in an uncertain and frustrated frame of mind.88 | ||

| The 480th Antisubmarine Group found in the Moroccan Sea Frontier a field especially well suited to its talents. Since the invasion of Africa on 6 November 1942, a major objective of the German submarine fleet had been to harry Allied convoys heading for Northwest Africa and Gibraltar. At first they had met with some success. On 11 November 1942, four merchant vessels and one destroyer were sunk while riding at anchor off Fedala (20 miles from Casablanca) by what appears to have been a mass U-boat attack. Allied aircraft, however, soon made hunting in these shore-line waters too costly for the enemy to continue. This work had largely been done by the British who made 37 sightings between 7 and 30 November, resulting in 21 attacks. By the end of December the PBY's had made 6 attacks in the area.89 The result was that the enemy retired to positions 400 miles or more from | ||

122 |

|||||||||||

| Casablanca and Port Lyautey. Instead of having to guard only a 200-mile span, the U-boats had then to guard an arc several hundred miles long; and for some time they actually took up positions along the arc of an approximate circle centered at Gibraltar. After January, all sinkings occurred more than 600 miles from the nearest aircraft base. During all this time the U-boats showed little tendency to approach within range of land-based aircraft, for, although thousands of hours were flown, no sightings were made until the arrival of the Liberators in March. These long-range aircraft were able to reach both the U-boats on patrol beyond PBY range and also those traveling the great circle submarine lanes to South America and South Africa. During the period March to June, a total of 12 sightings were made, mostly beyond the 400-mile limit. Meanwhile, aircraft operations from Casablanca had been discontinued and PBY's began patrols from Agadir in April.90 By June, the location of American antisubmarine forces in the Moroccan Sea Frontier was approximately as follows:91 | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Thus it became the peculiar task of the 480th Group to carry on long-distance patrols, beyond the extreme range of the PBY's, making the maximum use of the SCR-517 radar. Missions began promptly on 19 March in spite of temporary shortages of spare parts, maintenance personnel, and equipment.92 Three planes a day ordinarily went out | |||||||||||

123 |

|||||||||||||||||

| on operational missions, laid out by Fleet Air Wing 15, under the supervision of the Moroccan Sea Frontier at Casablanca. The area covered was at first from 31°00' N. to 35°00' N., extending west to the prudent limit of endurance (1,050 nautical miles).93 Later missions were ordered almost as far north as Cape Finisterre.94 Within 2 days of the beginning of operations, the group made the first sighting that had occurred in the area since December, and in the ensuing months of its stay at Port Lyautey it made roughly 10 times as many sightings per hour of flying time as the Navy PBY's operating from the same region at the same time. This result was owing in part to the extra range of the B-24, but also to the alert visual search of the B-24 crews and to the superior efficiency of their radar, which came nearer than the PBY equipment to making the theoretically expected number of sightings in the patrolled regions by a factor of 4.95 | |||||||||||||||||

| Of these sightings, all made in the period March to July 1943, inclusive, more that 90 per cent resulted in attacks on U-boats, and of these 20 attacks, 10 percent were sure kills. In all, more than 25 per cent of the U-boats attacked probably failed to reach port.96 Assessments run as follows:97 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| This fine record is largely owing to the high quality of flying technique and sound tactics employed by the pilots, to the well | |||||||||||||||||

124 |

||

| coordinated use of radar, and to the aggressiveness of the crews. Especially noteworthy is the use made of cloud cover. Clouds were available for use in 72 percent of the sightings, and were actually used in nearly 60 percent. In other words, of the 16 sightings in which cloud cover was available, it was used in 13 cases. Of the other 3, 2 involved flying below clouds on convoy coverage, and the other flying below clouds in darkness, both perfectly correct procedure.98 | ||

| As a result of superior flying technique, 16 of the 20 attacks were made while the enemy craft was still visible, and in 17 instances the U-boat was still fully surfaced or with decks awash at the time of attack. Here the B-24's again surpassed the B-17's for, in all out 2 of the 13 sightings made by the latter from November to 15 July the U-boats were able to submerge before the arrival of the aircraft. In one of these instances, the submarine deliberately chose to remain surfaced and fight back with AA fire.99 This result arose in part from the slower speed of the Navy planes and from less effective radar. | ||

| At least 13 of the sightings made by the group were first picked up by the SCR-517 radar equipment at an average range of 18 miles. At least 5 of these sightings would certainly not have been made without radar, and in 5 others the contact would otherwise have been doubtful.100 | ||

| The spirit of the crews played a very large part in securing the high record of attacks and kills. They showed general willingness to encounter enemy fire and an ability to carry out attacks in the face | ||

125 |

||

| of strong opposition. In six instances the submarines fired on the attacking planes, yet with the exception of the first case in which resistance occurred, the aircraft pressed home their attacks. Several planes were damaged by this sort of encounter, and about 12 crew members injured.101 | ||

| As in the Bay of Biscay, encounter with enemy aircraft in the Moroccan Sea Frontier proved more serious than resistance from the submarines themselves. As in the Bay, also, the early operations of the group were not seriously opposed by enemy aircraft, but, opposition became more and more severe as the effectiveness of the antisubmarine patrols increased. In the Moroccan Sea Frontier it was not the relatively short-range JU-88 that opposed the aircraft of the 480th Group but the powerful long-range FW-200, which in many ways is comparable to the B-24 itself. The first combat of this nature occurred in the last half of July, when the antisubmarine "blitz" conducted by the 480th Group during the first 2 weeks had goaded the enemy into desperate action. By August the FW-200's began to appear, heavily armed with rapid-firing 20-millimeter cannon which gave them as marked fire superiority over the B-24. From that point on, the crews of the 480th found their mission to be very hazardous, and the casualties increased rapidly. The final record is, however, one of which the group may be well proud, for, during its entire African operations, through October 1943, it is estimated to have destroyed 5 FW-200's, 2 DO-34's, and 1 DO-26; probably destroyed 1 JU-88; and damaged 2 FW-200's and 2 JU-88's. In doing so the group lost 3 B-24's | ||

126 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| as a result of action by enemy aircraft.102 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In all, the 480th Group put in a more than satisfactory amount of work in the Moroccan Sea Frontier prior to the dissolution of the Antisubmarine Command, even allowing for the excellent flying weather prevailing in the area. The following table demonstrates this fact:103 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This table demonstrates the relatively high proportion of flying time devoted to escorting convoys, a type of operation unlikely to produce many sightings of enemy submarines. From November 1942 to the middle of July 1943, no unthreatened convoy (defined as one having no plotted U-boat positions within 100 miles, or within 100 miles of the position for the ensuing 24 hours, was attacked.104 Conversely, of the 22 sightings made by aircraft in the area between 5 December and 15 July 1943 over 90 percent occurred within 80 miles of a plotted U-boat position. The average error was only 41 miles.105 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Facts of this sort confirmed the officers of the 480th Group in their belief that their aircraft would be more profitably employed in hunting in areas of high probability (defined as regions enclosed by arcs of circles, 80 miles in radius, drawn about predicted U-boat positions than in convoy coverage. They recognized, of course, | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

127 |

||

| that their very long range allowed them to pick up convoys much farther out than was otherwise possible, a practice which the convoy commanders greatly favored. And it was also true that a minimum of actual danger from unplotted submarines made a certain minimum of air coverage advisable on all convoys.106 Nevertheless, the results obtained in areas of high probability more than justified the diversion of as many planes as possible in those directions. Since such areas occurred mainly out of range of the naval planes (beyond the 500-mile limit) they fell principally to the Army B-24's107 As experience was gained, it became evident that by far the best ratio of hours per sighting could be obtained beyond 500 miles and on adroitly routed missions.108 As the Army became more and more influential, officially or unofficially, in routing patrols, a gradual improvement in that respect took place. | ||

| The campaign of 5-15 July, narrated above, gave the group a splendid opportunity to prove not only its fighting ability, but the validity of these tactical principles. Deployed on missions carefully routed toward those areas off the Portuguese coast where intelligence sources indicated the enemy had concentrated its forces, the aircraft of the group turned in what is probably a record for a unit of the sort.109 | ||

| The effect of this campaign of July may be estimated to some extent by the fact that, after 14 July, the 480th Group made no further contacts with enemy submarines during their stay on the west coast | ||

128 |

||

| of Africa. The Germans' attempt to defy heavy air coverage had proved disastrous to themselves and it was once again demonstrated that submarines either could not or would not operate in areas at all well covered by antisubmarine aircraft. In August patrols and convoy protective flights continued and were even extended. Employing tactics similar to those used by the RAF Coastal Command in July, a "shuttle run" was made in the early part of the month by the 2nd Squadron between Port Lyautey and Dunkeswell. On the trip to Dunkeswell the squadron covered a convoy and on the return flight it conducted an antisubmarine sweep, thus combining two principal functions in one operation. Two such runs were made in August, but no submarines were attacked.110 | ||

| The antisubmarine warfare in the Moroccan Sea Frontier generally may be similarly evaluated. Between the British squadrons at Gibraltar and the Navy squadrons in the Moroccan Sea Frontier, the Allied antisubmarine forces had, prior to the arrival of the Army B-24's, forced the enemy to withdraw from the immediate approaches to the vital area.111 The operations of the 480th Group forced them to withdraw to a point at which they could no longer seriously menace the convoys pouring through the Moroccan Sea Frontier, bound for the Mediterranean theatre. And in July, when convoys were sailing down from the United Kingdom to supply the Sicillian campaign, they were able to pass through the greatest concentration of U-boats then at sea without a loss from submarine activity, thanks to the effective air and surface escort provided.113 This relative immunity granted | ||

129 |

||

| finally to the Moroccan and Gibraltar area was a triumph for combined convoy escort and offensive antisubmarine sweeps, and it vindicated the principles underlying each form of antisubmarine activity within its own peculiar limits. | ||

| The operations in the Eastern Atlantic were experimental in a great many ways. For one thing, they gave the AAF Antisubmarine Command the opportunity to test its strategic doctrine. In the course of their rather brief duration, experiments were carried out in the difficult matter of administering the activities of units operating far from their parent organizations, and in the even more difficult problem of operational control. And, by no means least of all, invaluable experience was obtained in antisubmarine tactics in an area where operations had to be conducted on a more than theoretical scale. | ||

| As a result of these efforts, the AAF Antisubmarine Command was able to draw certain interesting, if tentative, conclusions. The offensive strategy had worked. If not the be-all and end-all of antisubmarine warfare, it had at least to be considered an essential element. In administration, the policy of sending units on detached service from the wing headquarters in the United States soon proved to be unsound and was replaced by one in which the overseas squadrons were given "separate, special" group organization. An effort had been made to extend that principle to the point of creating overseas wings, but AAF headquarters was opposed to expanding the AAF Antisubmarine Command organization on such a scale.113 Operational | ||

130 |

||

| control had been exercised over the AAF Antisubmarine Command units by both RAF Coastal Command and the U. S. Navy. The comparison was striking, and not always to the advantage of the latter. The AAF Antisubmarine Command had always recognized its British counterpart as a pattern, and the experience of actual cooperation under the operational control of the older organization had only confirmed the younger in its preference. Yet even in Northwest Africa the problem of naval control was greatly mitigated, if not exactly solved, as a result of the tact and vigor of the commanders involved. Finally, the detached antisubmarine units learned more in a week of operations in the eastern Atlantic about such things as defense against aircraft attack, proper attack procedures, and the use of cloud cover and radar equipment than they could have done in weeks of operations elsewhere. It was with a sense of anticlimax and frustration114 that they heard, in August 1943, that they were to be relieved of their mission just when they felt they were really achieving their objective and when they were, in fact, as efficient an antisubmarine team as could be found at that time. | ||

Operations in the Western Atlantic |

||

| The Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers. In contrast to the intensive, if sporadic, activity of the overseas squadrons, the story of antisubmarine operations in the western Atlantic is one of endless patrols, few sightings, and still fewer attacks. While the units of the 479th and 480th Antisubmarine Groups were enjoying the best | ||

131 |

||

| of hunting in the Bay of Biscay and in the Moroccan Sea Frontier, flying at worst only a few hundred hours per contact, units in many parts of the U. S. strategic area were flying many thousands of hours per sighting in regions with an average U-boat density of 1 in a million square miles of ocean. In the Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers almost no enemy activity had been encountered since September 1942. To the south and north, in the Trinidad area, and in that part of the North Atlantic convoy route lying off the coast of Newfoundland, the Germans were still trying hard to stop the flow of vital material. Even in those areas, however, the hunting was often poor. | ||

| Yet the Navy felt obligated to patrol not only these threatened areas but the relatively quiet waters of the Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers with as many aircraft as might be spared from other more urgent projects. The enemy, it was argued, had withdrawn, but he might return. He was not too preoccupied with the invasion convoys to overlook a rich and unprotected merchant shipping lane. And, as Admiral King put it, the submarines could shift their area of operation more rapidly than the air defenses could be moved to meet them. Accordingly, and "irreducible minimum" of aircraft would have to be maintained on the coast of the United States, despite the meager returns in contacts with the enemy.115 | ||

| The only question was, how small did that minimum have to be before it became truly irreducible? Was it necessary to provide such heavy coverage -- at one time as many as 15 out of 25 squadrons? | ||

132 |

||

| Was it an economical way of using units specially trained in the work of destroying submarines to deploy them in areas where there were few if any submarines, when in other parts of the Atlantic the undersea raiders abounded? These were debatable questions, the debate resolving itself finally into a conflict between the AAF Antisubmarine Command ideal of a mobile offensive force and the Navy's doctrine of a relatively fixed defense. Since the operational control of antisubmarine activity lay in naval hands, the Navy won the debate. The result was that many of the fully trained and equipped antisubmarine crews could say of their operations as one squadron historian said, somewhat wistfully, of his entire squadron: "The tactical achievement of the squadron cannot be elaborated on by enumerating the number of submarines sunk. It has been our misfortune never to have had the opportunity of sighting a submarine." When he added sturdily that "this fact has never reduced the crew's efficiency and patrol missions have been conducted in an alert manner," he epitomized as large portion of this story.116 | ||

| This work of patrol and convoy escort was shared by AAF Antisubmarine Command, air units of the U. S. Navy, and the Civilian Air Patrol. It must be remembered, however, that the CAP planes were light, single-engine civilian types, limited in their range to a narrow zone along the coast where the depth of the water normally restricted submarine activity, and that the planes used by the Navy in the Eastern Sea Frontier were mostly single-motor observation | ||

133 |

||

| types, with a limited radius of action compared to the Navy PBY and the medium and heavy bombers used by the Antisubmarine Command.117 | ||

| From October 1943 to February 1943, no damaging attacks were made in the Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers, and few positive sightings of enemy submarines. This startling lack of combat action was by no means the result of any reduction in antisubmarine patrol activity which remained heavy on the part of both Army and Navy squadrons. It was simply that there were few, if any, U-boats to see. From an estimated 10 enemy craft in August 1942, the average density in these areas had dropped in October to 3.4 and was further lowered in November to 1.7. In December, January and February there was no positive evidence of any enemy activity at all, though some depth bombs were dropped on suspicious spots in the water. In all, these operations during the winter of 1942-1943 probably did more damage to the aboriginal marine life in the patrolled areas than to the mechanized intruders. But there is no doubt that the negligible density of enemy submarines in its turn resulted partly from the continued heavy air coverage.118 | ||